The first Jewish settlements in Białowieża (half of 19th century to 1914)

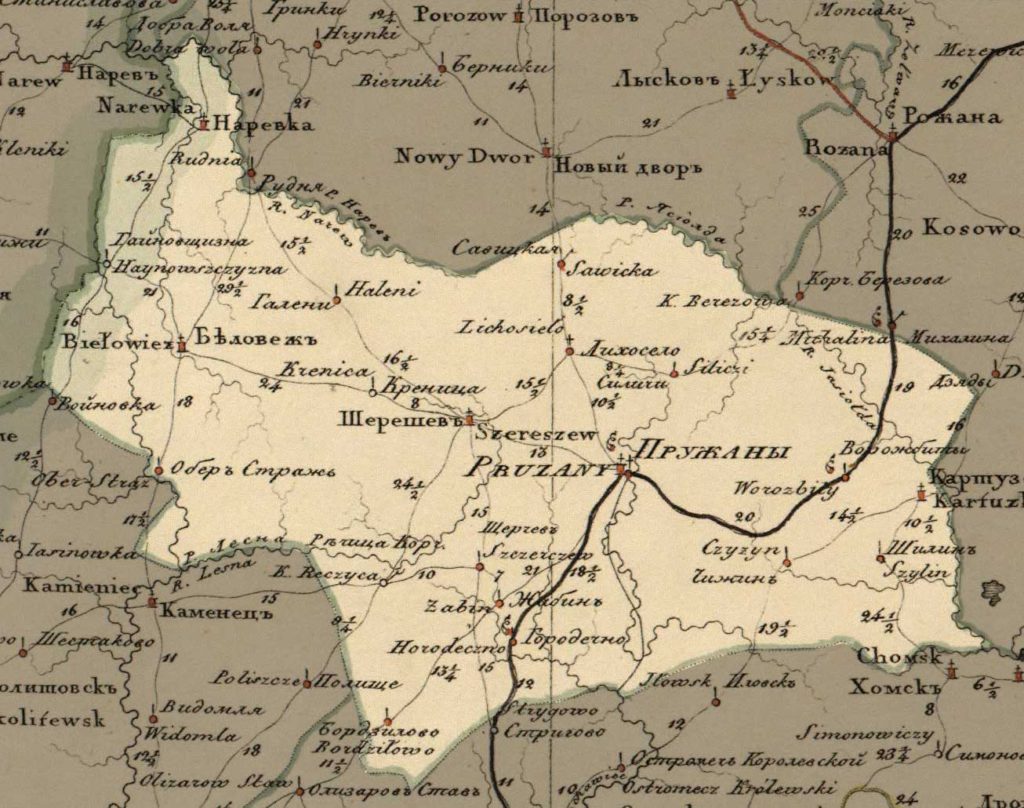

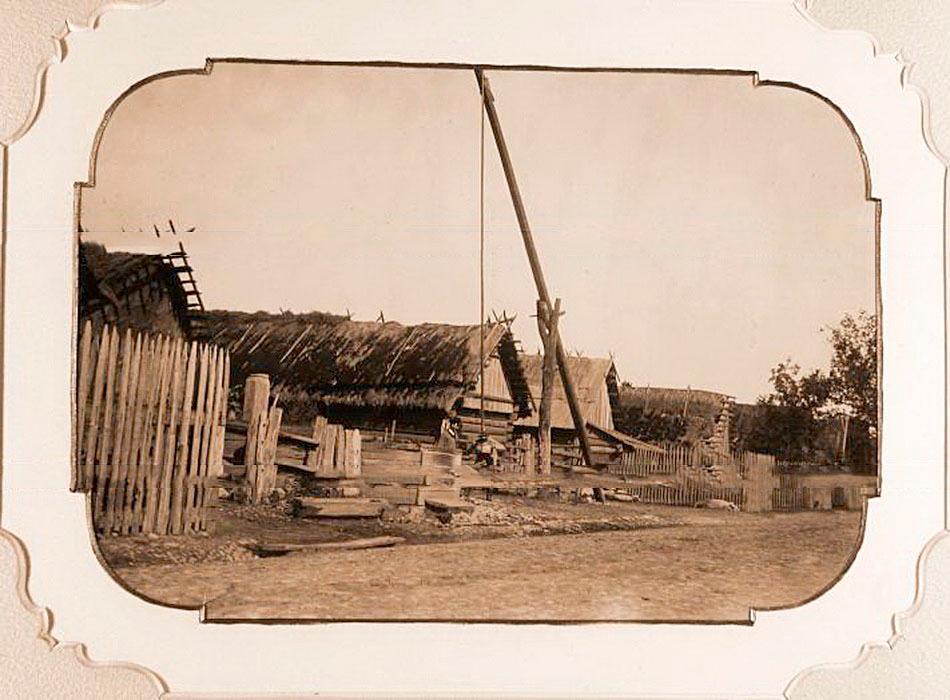

The first Jewish families settled in Białowieża in the first half of 19th century, before 1856, when Białowieża was a part of Russia – the Grodno Gouvernate, Pruzhany county (right now Grodno and Prużana are part of Belarus). For the Białowieża community, the main points of reference were the cities situated east of the city (currently in Belarus) – Shereshevo (35 km away) and the county city of Pruzhany (45 km away) which was connected with Białowieża by a forest route, called the "Prużański Route" until this very day (however, disused due to leading across the international border). The other trail through the forest, called the "Kamieniecki trail", connected Białowieża and Kamieniuki (25 km away), and also Kamieniec Litewski (45 km away) and Kobryń (95 km away).The first Jewish migrants to Białowieża came from the Grodno Gouvernate, which Białowieża was part of in these times. They were coming from the nearby Shereshevo [Szereszewo, Szereszów, Szereszowa] (in the end of the XIXth century, 4800 out of 9200 citizens were Jewish), Pruzhany, as well as Kobryń and Grodno. Most settled in the Stoczek village, which was in those days comprised of Waszkiewicz street (currently Białowieża's town centre) from the Osocznicy alley up to the Bartnicy alley. The village was closed from both sides with wooden gates, guarded in shifts by all of the adult members of the village (the men in the winter, the women in the summer) [14]. They lived in straw thatch cottages. [18].

1895, Studnia z żurawiem w jednym z białowieskich gospodarstw, zdjęcie z albumu Царская охота в Беловежской пуще.

The earliest information about Jews in Białowieża is found in the Memorial Book of Sokółka. From its pages we discover that prior to 1856, Jacob Mejer Halperin was the rabbi in Białowieża [1] . This means that one of the Jewish families had to settle in Białowieża at least few years before 1856 – to create the necessity of hiring a rabbi. In the Yad Vashem documents [13] and some testimonies of families [12] we find the surnames of several people born in Białowieża between 1865 and 1890, which means that their parents had to arrive some time before. Most of them were lumber traders– this is one of the professions mentioned by Wiszniakow, which in 1894 documents that Jews mainly dealt in small-scale trading, including the manufacture and selling of "bread wine", and that there was no transaction concerning wood without their mediation as they were known to be excellent assessors (appraisers valuing the price of wood) [11].

The oldest Jewish families in Białowieża from this time are:

- The Burnsteins - Avraham Burnstein was born in Białowieża in 1865, he became a lumber trader, and his family is present in the further history of Białowieża.

- The Tenenbaums -Beiła Tenenbaum, the daughter of Meier Tenenenbaum was born in 1865 in Białowieża. She married Avraham Burnstein. There are no records of the family in the midwar period.

- The Salmans - Yakov Salman, the son of David Shlomo and Dora Chana Salman is born in 1870 in Białowieża. He became a lumber trader.

- The Sztejnbergers (Steinbergs) - Yakov, the son of Chana and Elijahu Sztejnberg is born in 1878 in Białowieża.

- The Halperins (the Galperns) - Jeszua Halperin came to Białowieża in the II half of the XIXth century from Grodno. We know for certain that his children were born in Białowieża – daughter before 1892 and son, Lazar in 1892. Jeszua was an owner of a wood sorting department. The descendants of Halperin currently live in Israel – two of them had visited Białowieża in 2016 [12].

- The Feldbaums – a young married couple, Aaron and Judith Feldbaum come to Białowieża from Szereszewo (Shereshev) in 1875. They buy a house on the main street Stoczek (at that time, in the village of Stoczek). Aaron will soon become a very important member of the society, which we can see in the farewell letter that the Jewish Community of Białowieża prepared when Aaron was immigrating to the USA in 1921. Aaron was one of the prime initiators and founders of the synagogue in Białowieża. The numerous Feldbaum family immigrated between 1900 and 1920 to USA and Canada, where their descendants live to this today.

- The Talmuds – Israel Talmud was born in Białowieża in 1884.

- The Klejnermans (the Kleinermans) – Nachman, the son of Szlomo and Dora Klejnerman was born in Białowieża in 1890. He became the owner of a grocery store.

- The Poczynkos – Bracha Poczynko, the daughter of Izaak and Szoszana Poczynko, was born in Białowieża in 1898.

The Grodno archives contain documents mentioning Jews who had insured their buildings in Białowieża in the years between 1895 to 1898. El Leibow Steinberg insured two houses and a pigpen in Zastawa – the first house for 60 roubles, the second house for 300 roubles and the pigpen for 10 roubles; Szmul Ratowiecki insured his house for 80 roubles and his pigpen for 10 roubles. In Stoczek, Berko Krugman insured his house for 8 roubles, his pigpen for 5 roubles; and Icko Lerenkind insured the house for 100 roubles and the pigpen for 8 roubles [3].

The county office for industrial tax in Pruzhany mentions Naftaly Lipkowski and Abram Burnstein among the taxpayers united in the merchant guild, recording them as citizens of Białowieża handling the production and sales of poultry feed [4].

Towards the end of the 19th century, Białowieża started to expand intensively as a result of the adjunction of Białowieża Forest to the tsar's appanages in 1888. In between 1889 and 1894, the tsar of Russia Alexander the Third ordered the erection of the Hunting Palace in Białowieża and its premises, a brick Orthodox Church (preserved to this day); and a housing settlement for the officers of the Appanage Administration in the Dyrekcyjny Park. [t/n: landscape park in the Białowieża Forest]. The movement of migrant workers resulted in the settling of Jews in Białowieża, who would very soon be opening their first stores. "The Jewish nation would arrive here in the 1880s, during the construction works on the tsar's palace and the buildings in the Dyrekcyjny Park. Most of them weren't working at the construction site itself, but came to trade, as Białowieża was at this time a gathering of the nation, there were so many workers. A number of private buildings were erected in Stoczek, before they did not reach past the Osocznicy alley, and by the end of the 19th century they began to build even further (…). There were three lumber mills. Stock was brought by the Białowieża cart drivers. There were plenty of people, and plenty of work in the forest to build such a house – disposal, logging, preparation of the wood, transporting, processing and woodwork" [24].

In the 1890s, Białowieża was the headquarters of the administrator of the Białowieża Forest and the head of the municipality (voyt). There were two folk schools in the city, a clinic and a post office. Piotr Bajko relates that Białowieża at that time had 121 houses, including the villages of Stoczek (56 houses), Podolany (28 houses), Zastawa (32 houses) and Krzyże (5 houses), with around 600 citizens [5] – the sources for this data are not mentioned, however, and the numbers seem severely underestimated.

The Geographic Dictionary of the Kingdom of Poland and other Slavic Countries published in 1895 states that Białowieża already boasted of 56 houses at the reign of king August the Third, so about a hundred years earlier [25]. As for the villages – Zastawa is mentioned with 38 houses and 181 villagers [25], while Stoczek and Podolany are noted without any data and Krzyże (figuring in the dictionary as "Kryże") is called a "wilderness next to the village Zastawa" [29]. The dictionary had various editors, its contents often based on material sent straight from the place of interest, therefore having different levels of substantial value – which the editors themselves admit in the preface.

Another source from that time is the Russian Census held in 1897. The census gives us the information about 886 people living in Stoczek, of which 749 belonged to the Orthodox faith; Zastawa – 596 inhabitants of which 544 belonged to the Orthodox faith. In total, Białowieża was inhabited by at least 1482 people, of which 1293 belonged to the Orthodox faith [30]. The census only considers villages with at least 500 residents, which explains the absence of Podolany and Krzyże. The group which interests us the most are the 189 inhabitants with no stated religion – we can suspect that most of them held to the Jewish tradition, as Catholics began to arrive in Białowieża en masse only after the First World War. In these times, Catholics were a group small enough that they belonged to the parish in Szereszewo – a Catholic parish in Białowieża was founded only in 1926, with the church being consecrated in 1934 [31].

From the testimonies of the Feldbaum family we learn that when they were living in Białowieża (1875-1920) there were around 30 other Jewish families there as well – so, close to 100 people; although we are not sure of the exact years out of the 40 [2]. Georgij Karcow writes in 1903 that "more than 3/4 of the inhabitants of the Forest [Ed.: with that word he refers to the whole territory, not just Białowieża] are Orthodox, around 12% of them are Catholic, and about just as many of them are Jewish" [10].

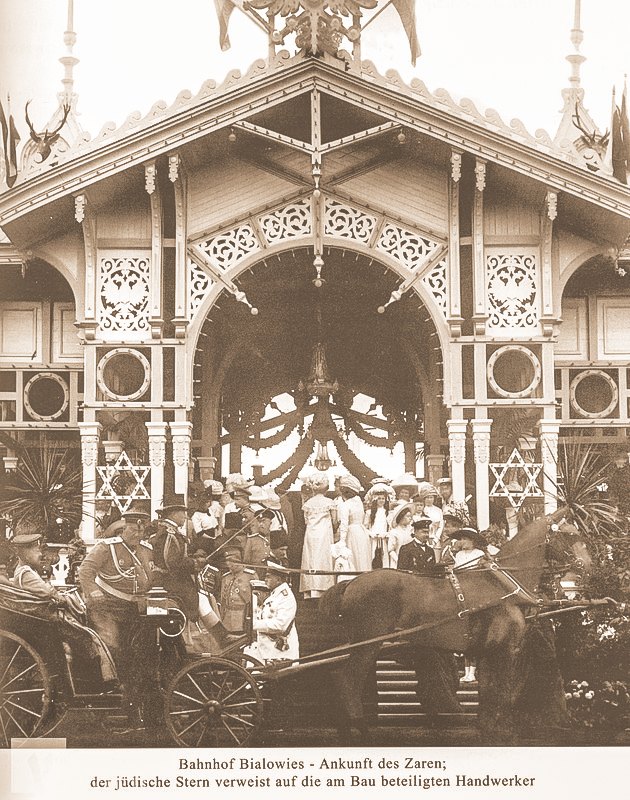

Carski dworzec kolejowy "Białowieża Pałac" pobrane ze strony Wirtualny Sztetl Podpis pod zdjęciem "Przybycie cara do Białowieży, gwiazda Dawida wskazuje na udział żydowskich rzemieślników w budowie dworca"

![Stacja kolejowa Białowieża Pałac 1895, Carski pawilon w dzień przyjazdu cara Mikołaja II i jego świty [fot. z albumu Царская охота в Беловежской пуще]](http://www.jewish-bialowieza.pl/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Stacja_kolejowa_Bialowieza_Palac_1895-Carski-pawilon-w-dzień-przyjazdu-cara-Mikołaja-II-i-jego-świty_-Fot_-z-albumu-Царская-охота-в-Беловежской-пуще-1.jpg)

Stacja kolejowa Białowieża Pałac 1895, Carski pawilon w dzień przyjazdu cara Mikołaja II i jego świty [fot. z albumu Царская охота в Беловежской пуще]

The construction of the Palace was the reason to build a railway connecting Białowieża with Hajnówka (built between 1897-98) and from 1907 with Siedlce and Warszawa. The railway had two stations – Białowieża Towarowa and Białowieża Pałac. Contrary to the reports of Jan Sawicki, Jewish workers took part in the construction of the Białowieża Pałac station, an act which was commemorated by embedding two Stars of David in the main gate's architecture. The current reconstruction of the Białowieża Pałac station doesn't include this element; whereas the Białowieża Towarowa building has been fully preserved and currently holds a restaurant venue.

In 1903, a modern highway was built, connecting Białowieża with Hajnówka and Bielsk on one side, and on the other side with Pruzhany [9]. Białowieża's new accessibility resulted in many Jewish families coming from the west – we know for sure about two families which moved there from Warsaw at the beginning of the 20th century – Sznabel and Cynamon, and the family Skałka which moved from Siedlce.

It is unknown when exactly, but the first synagogue was built before the First World War – it was a wooden synagogue in Stoczek. After WW1, a private prayer house in a brick building was built on the same street [6]. There was also a school for boys – a cheder [7]. It is uncertain which cemetery was used for the burial ceremonies – Piotr Bajko claims (probably based on testimonies of the oldest inhabitants) that there was a cemetery in Szereszewo before the First World War , but in Pinkas haKehilot we find information about a cemetery in Narewka [7]. There are no sources concluding which of the cemeteries was in use. It is also not known which religious group of Jews the inhabitants of Białowieża belonged to – though there are some clues indicating they may have been Misnagdim.

In addition to selling and pricing the wood in the middle of the 19th century, Jews took the positions of tradesmen, craftsmen. They also bought out honey and wax from the beekeepers, up until 1897 when the tsar prohibited beekeeping. Jan Karpiński, based on the interviews he held with the last beekeepers in the '30s of the 20th century writes: "Jews were buying out the honey and the wax in the villages. For a full wooden jug they paid from 2 roubles upwards, and in outstanding situations, the price of good linden honey could go up to 15 roubles for a pot. Wax in honeycombs was 5 zlotys (75 kapiejkas) per pound. They also bought the after-wax production remains" [17].

An inhabitant of Białowieża, Borys Rusko, recounts two families noted in Białowieża "at the time of the Tsar" which his father, Emillian Rusko, mentioned in his stories. Kuszel Lubietkin lived in a forester's lodge in Podolany before the First World War: "Kuszel lived for some time next to the Terebenthen, or the tar-house [Ed.: more likely next to the tar-house as the Terebenthen was founded by Germans in the 1915]. It was on the crossroad of this way which goes from Podolany to the border and the Pruzhany road, the road that leads from Białowieża. On the crossroad of these two roads before the war, [Ed: before the First World War] at the time ot the Tsar, there were buildings where the workers who carried the wood could live. Kuszel probably had a job transporting turpentine, or something like that. From there, from that place, he came to Podolany" [19]. In 1922 Kuszel moved to Podolany. The other family that Rusko remembers are the Słonimskis: "Słonimski was also living there [Ed: in the forester's lodge in Podolany]. Before the First World War, his son was studying in Petersburg, at the mathematical and astronomical institute. My father told me about that, because he was often visiting his sister, flirting with her. They were very open and friendly, he said they were a very nice family" [19]. The Słonimski family moved then to Białowieża, to the Zastawa district [20].

Pierwszy z prawej - Aaron Feldabum, z matką Zeldą i bratem Nachmanem, 1875, prawdopodbnie przed wyjazdem Aarona w tym samym roku do Białowieży. Zdj. ze zbiorów rodziny

For a period of about 20 years, wood trading ceased to be good business in Białowieża. In 1888, the Białowieża Forest became attached to the Tsar's private property, and was designated as a hunting territory for him and other dignitaries. Exploitation of the forest had to be limited, and finally halted in 1897 – the very same year in which beekeeping was prohibited. [15; 16; 17].

At the beginning of the 20th century more Jewish families moved to Białowieża, some from Siedlce and Warsaw. However, part of the settled families decided to emigrate just like many Jews living in Russia due to the unfavourable politics of Tsars Alexander the Third and Nicolas the Second. From 1882 till 1917 many restrictive bans were imposed on Jews, such as the prohibition of settling and buying land, as well limitations in choice of career and education opportunities and visible discrimination in the army. The bureaucracy and the nobility were also hostile towards Jews, blaming them for the destructive fallout of modernisation and industrialisation. After tsar Alexander the Third was assassinated in 1881 by a group of revolutionaries, a wave of anti-Jewish pogroms committed by peasants rippled across Russia and the Polish Kingdom (1881-1906). In the Grodno Gouvernorate, which Białowieża was a part of, ten pogroms were noted, in which 365 people died. The biggest pogroms took place in Białystok (1906) and Brześć (1905) [32].

This whole situation caused a mass emigration of Jews from the Russian Empire territory. Most fled to the United States, but also to Great Britain, Argentina, Canada, Palestine, France and Southern Africa (place of emigration of the Kiszyszki community, likely the family of the Białowieża rabbi Kopel Kahana).

There are also records of pogroms in Narewka, a mere 18 kilometres from Białowieża. Leon Leyson from Narewka, a Holocaust Survivor from Schindler's list writes in his book: "Protected by the love and care of my family, I didn't know much about the oppressions which fell on the Jews in Narewka. My parents survived the pogroms at the beginning of the 20th century, when this part of Poland belonged to Tsarist Russia. After these incidents, many Jews from our surroundings left for America (...)"[33].

There is no information about a pogrom happening in that time in Białowieża. Nevertheless, the harsh conditions of life in the end of the 19th and at the beginning of the 20th century together with the unsettling news coming from the neighbour villages became reason enough for most of the Białowieża families to emigrate. Certainly this was the case of the numerous family of Aaron and Judith Feldbaum. The first member of the family to move to the USA was the husband of Małka Feldbaum, Chaim Aaron Schneider, a soldier of the Tsar's army in 1901. His family wanted to save him from being sent to the front line of the upcoming Russian-Japanese war. By the outbreak of the First World War, four more Feldbaums moved to the USA. We do not have data concerning other families, but we can suspect that the families of Tannenbaum, Ratowicki and Lipkowski made similar escapes, as their surnames, present in the end of the 19th century, do not appear in any sources concerning the interwar times in Białowieża.