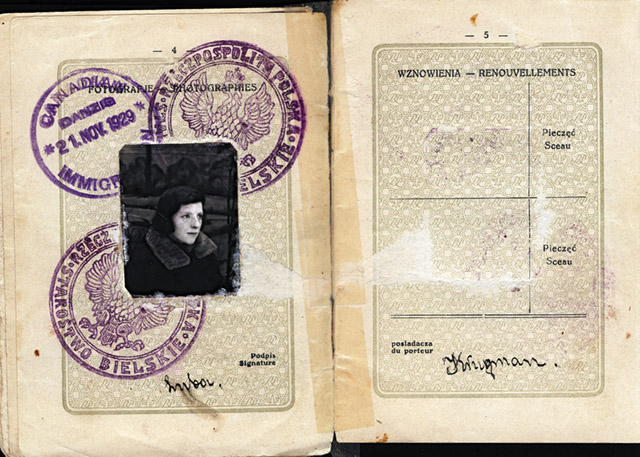

One such settler was Abram Mordechajewicz Jelizarow, a deserter from the tsar army arriving in Białowieża at the very end of the First War. Abram Jelizarow was of Caucasian provenience, and he was the father of Gawrił Ilizarow, born in 1921, a well-known Soviet orthopedist. Abram returned to his hometown Kurgan in Dagestan in 1930, together with his wife Golda and five kids. In 1920 the Polish government recognised the Białowieża forest as a terrain for planned forest management, resulting in the creation of the National Forest Holding Committee in 1921 and reactivating the lumber mills in Stoczek and Grudki [1]. After the government gave concession for logging to an English company „The Century European Timber Corporation”, a massive scale exploitation of the Forest began. The sudden development of the wood industry caused mass migrations to Białowieża and Hajnówka (which developed from a village into a large worker's town). The migrants were Catholics, working in lumber mills and factories, and Jews, dealing with the trade of wood and various goods as well as craft and services. The first official census held by the Polish government in 1921 gives us specific information about how many Jews lived at that time in Białowieża – all together there were 143, out of 1811 citizens, which makes up 7,9% of Białowieża's population. 112 out of 1064 citizens were of Jewish faith in the Stoczek village, 15 out of 342 in Zastawa, 10 out of 87 in Krzyże, 6 out of 8 in Podolany Leśniczówka, and 0 out of 310 in Podolany, although we know that the very next year a Jewish family Lubietkin moved to that village, changing the count. Three worker's settlements were not mentioned in this tally – the lumber mill in Grudki (3 people out of 150), the lumber mill in Stoczek (102 people) and the factory neighbourhood in Stoczek (144 people) [2]. The data which can be found in several research papers [3] mentioning 217 people instead of 143 relates to the whole of the Białowieża borough (at that time, 70 towns and 6674 inhabitants), so it also includes the 40 Jews from Hajnówka. Obviously, these numbers changed rapidly due to the constant rise of population (newborns, returns of natives who had fled to Russia, migration within the country). Podziękowanie Aaronowi Feldbaumowi przygotowane przez społeczność żydowską w Białowieży w dniu wyjazdu Aarona i Judyty Feldbaum na emigrację w 1921 roku. 1921 is also the year when the previously mentioned Aaron Feldbaum left Białowieża, which we find out from a farewell letter signed (according to Aaron's grandson) by the most important Jewish families in the community. Signatures: My, mieszkańcy Białowieży, z okazji pożegnania i rozstania z panem Aaronem Feldbaumem, wielkim filantropem, przywódcą społeczności i gospodarzem, który teraz wyjeżdża do Ameryki, chcemy złożyć mu najlepsze życzenia płynące z głębi naszych serc. Ze łzami wdzięczności chcemy wyrazić uznanie dla działań tego pacyfisty, które podejmował podczas całego 40-letniego okresu mieszkania w Białowieży. Dzięki temu dobroczyńcy wybudowaliśmy synagogę; Dzięki niemu ludzie biedni, wdowy i sieroty znalazły schronienie w krytycznych momentach. Pióro nie ma siły, aby opisać zalety tej osoby. Bez przesady można powiedzieć, że jego odejście pozostawi pustkę i smutek w sercu każdego mieszkańca Białowieży. Będzie go wszystkim brakowało, a zwłaszcza tym bezbronnym, którym szczordą ręką stworzył możliwości odbudowania swojego życia. Wtorek, XIX Adar II 5681 [wtorek, 29 marca 1921]. Izaak Tennenbaum tłum. z angielskiego: Katarzyna Winiarska In 1925 Wiktor Szymański writes in the "Short guide through the Białowieża Forest": „according to the census in the Białowieska settlement [on previous pages Szymański clarifies that Białowieska settlement is in fact Stoczek village] there are 2892 inhabitants. (…) There are quite a lot of Jews in Białowieża, who live here as tradesmen, store-keepers and workers of forest industry companies. In relation to the rest of the population, Jews make up around 10% of the inhabitants" [6]. It is unknown on which census Szymański based this number of 2892 inhabitants in the Stoczek village, as after the 1921 census which marked 1064 people in Stoczek, there were no official records until 1930- unless a local census was performed. We know of several Jewish surnames from the late 1920s, tradesmen and craftsmen found in Polish directories published between 1926-1930 [7; 8; 9]. The list of Jewish tradesmen, craftsmen and servicemen is very long. Jews from Białowieża were mainly owners of: grocery stores, among them most famously Klejnerman, Małecka and Szuster; fabric stores – Samuel Alkon; haberdasheries – Rachela Nowokolska; and so-called „iron-stores” with Tabacznik and Stawski leading the market. Jewish surnames can be also found among occupations such as dentists (Gołda Topolańska), lawyers (Frydberg Izzak), hairdressers, tailors, shoemakers, blacksmiths. Many of them rented rooms or worked in the popular wood-industry, owning lumber mills and trading wood. In all testimonies Jews are portrayed as efficient businessmen who would not only efficiently encourage you to buy the product, but also lower the price and offer beneficial instalments or credit, without taking interest. Włodzimierz Dackiewicz remembers it as follows: "Just after the First World War, the migration to Białowieża was enormous, and Białowieża [borough] had 13.800 inhabitants. The Jewish communities also arrived in Białowieża – many of them, probably more than 500-600 people. They mainly worked in crafts: there were tailors, shoemakers, carpenters, locksmiths, and they also worked in trade. They felt at home at our place in Białowieża, because they were very noble people – they offered you credit and didn't take any interest. When you went into a shop, sometimes without any money, and a product was luring you, was interesting, they were encouraging you, signing you up in a notebook, and you paid when you had money without any extra percent. That's why the Jewish communities in Białowieża had a lot of trust among the people" [23]. The list of Jewish tradesmen, craftsmen, contractors and representatives of other professions in Białowieża that we managed to array: The list mainly refers to the interwar period, but some of the surnames are from the period from the middle of 19th century till the First World War. The shops were divided by branches, although as many of them offered mixed services and products (groceries and haberdashery; petroleum or metal, often transport services, train-ticket selling etc.), while reading the list it's important to remember that the same surname might appear in many categories, which I tried to mark down. Next to some of the shops there is an clarification of the district or of the street – Zastawa, Tropinka or Podolany. If there is no remark, it means that the shop was on the Stoczek street. Office workers: Teachers: Pianists: Lawyers: Dentists: Students/highschoolers: Grocery stores: Bakers: Tailors: Tailors (women): Silk stores: Haberdasheries: Haberdashery: Shoe stores, shoemakers: Wood trade: Butchers, meat stores: Soldiers: Vendors (unspecified): Beer taverns/restaurants: Hotels: Transport services: Iron and building articles: Późniak Forgehouse: Hairdressers: Industrial articles: Saddle-makers: Furrier: Photographer: Locksmith: Electrician: Carpenter: Glazier: Bath-house: Milk-man: Fuel station: (where the monument under the Orthodox church is now) Fajber Zyngier Zdjęcie rodziny Galpernów (Halperinów) w Białowieży pod sklepem prowadzonym przez Idę Galpern (siedzi). Zdjęcie ze zbiorów rodziny As new Jewish families were coming to Białowieża toward the end of 1930s, others would decide to emigrate due to the decline of the economy caused by high taxation of small grocery stores and tradesmen. Most Jews were forced to close their shops [5]. In his letter from 1935 written to his sister Matilda, who lived at that time in Palestine, Abram Lerenkind from Białowieża mentions an intentional strategy of pushing Jews out of the trade . He points out the activities in Białowieża itself together with the general tendency in the nation. He writes: „You can already feel the wind of change in Poland, trying to limit the Jewish activity in the economy. It is happening everywhere – with help of the Polish officials there are cooperatives established even in the smallest villages; and the agitation to push the Jews out of the trade and craft is rising. The [illegible: front office] in Białowieża organised a cooperative next to the forestry management, where they plan to reroute trade of all kinds of articles. They are putting heavy pressure on all of the officials” [11]. Abram Lerenkind was likely speaking about a general-grocery shop opened in May 1935 (the letter is from June 1935) by the Forester's Family Association (Koło Rodziny Leśnika), a section of the Forester's Trade Union, dedicated to their members and forest workers [12]. The Forester's Family shop was opened also in the worker's district in Grudki. „Just before the war broke out, the Forester's Family shop was opened, a cooperative was established next to the lumber mill, and a Jewish milkman brought milk to the settlement every morning” as Piotr Bajko wrote in „Echa starej Białowieży” (Echoes of old Białowieża) [18]. In the '20s and '30s, a zionist movement develops strongly in the area. Organisations such as HeChalutz and HeChalutz HaTzair which prepare the young to move to Palestine and live in the kibbutz and other zionist organisations like Hashomer Hacair, Mizrach, and Betar were active in all of the neighbour towns – Prużany [13], Szereszewo [14], Kobryń [15], Narewka [5] and Bielsk Podlaski [16] – a most important town for Białowieża in that period, as Białowieża belonged to the Bielsk poviat. There were zionist schools, preschools and middle schools teaching Hebrew (for example Tarbut preschool in Bielsk, which Rachela Barchat, the daughter of Matylda Lerendkind from Białowieża attended) and many special camps on designated farms, intended to teach agricultural skills to potential immigrants. We don't have any information about zionist movements in Białowieża itself, but we know of people who emigrated during that time to Palestine. Szejna Halperin z dziećmi i Chaja Halperin wiele lat po emigracji (1968) na swojej farmie w moszawie Kfar Yehoshua w Izraelu Szejna Halperin (Galpern) and her sister Chaja Halperin (Galpern) left in 1926 to a city called Nahlat Yehuda, where they started working. After Szejna got married in 1933 to Jacob Kartzinel from Kobryń, they moved to moshav Yehoshua where their descendants live to this today. Szejna's friend, Avigail Reines from Białowieża, from a prominent family of XVII and XIXth century rabbi's from Lida and Pińsk (family name Reines) finished middle school and continued her education in a HeHaluc school, although it's uncertain in which city – probably in Bielsk. Like most of the young people belonging to the HeHaluc movement, she took part in Hachshara camps in which they prepared for pioneer life and managing a household in Palestine. After two years training in a Hachshara in Łuck she left for Palestine in 1939 as an illegal immigrant, and moved into kibbutz Yagur, 9 kilometres away from Haifa. Druga dziewczynka z lewej Rachela Barchat, córka Matyldy Lerenkind z Białowieży, w przedszkolu Tarbut, Bielsk Podlaski 1937 r. Matilda Lerenkind from Białowieża also emigrated to Palestine. Matilda had previously moved to Bielsk, which was her husband Chaim Barchat's home town. The Barchat family was very involved in the zionist movement, strongly supporting the youth organisations working towards aliyah to Eretz Israel (emigration to Palestine), teaching children in Hebrew schools (their daughter Rachela was enrolled in the Tarbut preschool in Bielsk) and they were planning to move to Palestine with their whole family. Chaim and his brother Israel traveled there several times, and finally moved towards the end of the '30s. He moved to Tel Aviv together with his wife Matilda Lerenkind, their daughter Rachela and his brother Nathan, planning to set the ground for the rest of the family. War broke out shortly after their arrival. Their descendants are still living in Tel Aviv. Alexander Burnsztein and his cousin Ezriel Alkon who was still a child in those days also moved to Palestine, and settled in Haifa. Other members of the Halperin family moved as well, for example the brothers of Szejna – Lazar Halperin who moved to Ukraine in 1920, and Szajla Halperin who moved to Australia. Two brothers and two sisters of Majer Loszewicki from Białowieża emigrated to Argentina. In 1927, the Ministry of Culture and Religious Beliefs issued a regulation concerning creating district divisions of Jewish Communities in the following counties belonging to the Białostockie voivodeship: białostocki, bielski, grodzieński, sokolski and wołkowyski. A Jewish community district was created in Narewka Mała, adjoining the Białowieża borough. Other towns to join the community were Narew, Łosinka and Masiewo [10]. (Of course this does not mean that Jewish community structure – kehilla – didn't exist before in Białowieża.) For that reason, the synagogue built before the First World War was thoroughly renovated in the 1920s. [19]. Despite so many Jewish families emigrating, the wave of Jewish immigration to Białowieża was a constant, increasing shortly before the beginning of the Second World War. Unfortunately there are no precise demographic data applying to the 1930s. The census from 1931 doesn't give any data on the level of towns, but only on the level of boroughs – so we know that in the borough of Białowieża (70 towns, among them the rapidly developing Hajnówka) the population increased from 6674 to 18.231 citizens [17]. There's no data concerning religious beliefs and nationality. In 1933 in the „Short guide through the Białowieża Forest” (Krótki przewodnik po Puszczy Białowieskiej) Jan Kłoska writes: „The population of the forest villages is mainly Russian, partially Mazurian. The orthodox Russians are almost all of the citizens in the villages surrounding the forest. They were strongly russified during over a hundred years of Russian reign in this territory. They live in four villages on the Białowieska clearing [Krzyże, Zastawa, Stoczek, Podolany], although here there's as well a big mix of Jewish and Polish immigrants. As the natives of these four villages mainly work in agriculture, the newcomers, who mainly arrived after the First World War are recruited to be forest and factory workers [Poles], tradesmen and merchants [Jews]” [20]. Before the war Jews still lived mainly alongside the Stoczek street (currently Waszkiewicza), but plenty of families also made their homes in the Zastawa district (currently Zastawa and Olga Gabiec streets), Krzyże, and a single family in Podolany. Most of the inhabitants relate that every second or third house on the Stoczek street is a house previously inhabited by Jews. Some of them they owned outright, some of them were rented. Because most of the Jewish houses held store or a craft shop, they were situated with their facade and entry towards the street, unlike typical Belorussian houses. That is one method of recognising old Jewish houses. Some of them lost this characteristic after the front door was taken out and replaced with a window or boarded up. The Jewish houses were also decorated differently, as Sławomir Szpakowicz reminiscesn [22] although there are no traces left of these ornaments as they were removed by the new house owners. When comparing pictures of a pre-war building, serving as well as a private prayer housem with its current look, we can easily see all of the changes – dismantling of the door and the balcony, removal of the ornaments. Tomasz Wiśniewski reports that in 1937 there were 4000 inhabitants in Białowieża, with 10% of of Jews, and in 1939 after the 17th of September – 550 Jews [21]. There is no information about the sources for this data. Moszaw - osada, jaką tworzyli syjoniści przybywający do Palestyny na początku XX wieku. Moszawy podobne są do kibuców, nacisk kładzie się na pracę społeczną, jednak różnią się od kibuców tym, że mieszkańcy mogą posiadać własność prywatną. Rolnicy zajmują się uprawą na własny rachunek, jednak płacą na rzecz społeczności specjalny podatek, równy dla wszystkich mieszkańców.

Jewish settlements during the mid-war times (1918–1939)

Niech lider wspólnoty, pan Aaron Feldbaum, i jego rodzina, wyjadą w szczęściu.

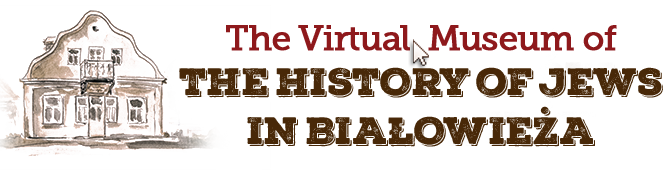

Chaim Krugman

Josef Prinz i Abraham Printz

Abraham Lilenthal

Mendel Burstein i Abraham Burstein

Benjamin Hoffman, szames/szkolnik w małej jesziwie

Yael z Szereszewa, syn sędziego

Eli Steinberg

Izaak Jakub, syn Eli Chaima Szteinberga

Natan Szymon Stawski i Jakub Stawski

Szewach Ruben (Rubin)

Welwel i rebe Chaim Nowokowski

Józef Sawczycki

Abraham Mordechaj Jalecki

Pisarewicz Mosze

Szrajbman Mosze

Sztejnberg Chanoch

Sztejnberg Szlomo

Szwach Łozer

Papisz Aszer (moved to Stolin)

Alkon Estera (Edka)

Frydberg Izaak

Topolańska Gołda

Alkon Donia (highschooler)

Halperin Lazar

Słonimski (before the First War on the University in Petersburg)

Sztejnberg Abram

Sztejnebrg Pinkas

Anisimowicz Sosza

Bachrach Sara

Bler M.

Boczan (Bocian) Sima

Byszko

Cienki Natan - groceries and haberdashery; iron articles

Cynamon Jakub - groceries and household articles

Frost J.

Goldberg Szaja - groceries and a beer tawern

Grabski Szloma Zelman - groceries, iron articles and silk materials

Hofman Abram (Czerlonka)

Jelizarow Abram

Klejnerman Mejer - groceries and silk materials (Zastawa)

Klejnerman Nachman

Klejnerman W.

Klejnermann Kejla - groceries and haberdashery (Zastawa)

Kraśniański Chaim (Czerlonka)

Krugman W. (Zastawa) - groceries and wood-trading

Lejenmand I.

Lejman Bencjon - groceries and haberdashery

Lejman I.

Liniewska Sara - groceries and haberdashery

Lubczyk Roza

Lubetkin Frejda i Kuszel, potem Judel (Podolany)

Malecka Leja - groceries and silk materials

Malecka Mirjam - groceries and haberdashery, silk materials

Malecki Chaim - groceries and transport services

Malecki Łazarz

Mejer (Zastawa)

Narbar G.

Norba (Narbar) Genia - groceries and grain selling

Prync J.

Rabinowicz Motel - groceries and transport services (Tropinka)

Rozencwajg I.

Słonimska Rachela (Zastawa)

Stawski Jakub - groceries and haberdashery

Stawski L.

Stawski Sz.

Szewiec Ch.

Sznabel Zelig - groceries, and a hotel with an restaurant

Szrajbman Chana - groceries and silk materials

Szrajbman Sara - groceries and silk materials

Szurkman R.

Szuster Aron (Zastawa)

Tabacznik Salomon - groceries and iron articles

Wołkostawski Lejb (Zastawa)

Zając Mejer (Zastawa)

Birnbaum, f.

Funke (Wojciechówka)

Prync Abraham

Wolmel W.

Boczan Aszer

Cywiński

Dawidowicz M.

Machleder Lejba

Malecki Izrael

Nowokolski W. - tailor, haberdashery and silk materials store

Szlejfer

Winokur I.

Będner Tajbl (po mężu Reines)

Burnsztejn Mina - dziewiarka

Feldbaum Roza

Rabinowicz Doba

Rabinowicz Rywka

Sawczycka Fejga

Sawczycka Rachela

Sawczycka Rywka

Sawczycka Szewa

Skałka Róża

Alkon Berta

Alkon Samuel

Goldking Kopel - silk materials and a beer tavern

Grabski Szloma Zelman - grocery store, iron articles and silk materials

Kadysz Jejna - textile store

Liniewska Sara - groceries and haberdashery

Malecka Leja

Malecka Mijam

Nowokolski W. i Nowokolska Rachela - haberdashery and silk materials

Słonimska Pola

Szrajbman Chana

Szrajbman Sara

Drozdowska Chana

Galpern (Halperin) Ida - haberdashery, tobacco store, train ticket store

Grabska - herbadasherie, silk materials, grocery store

Lerenkind Abram - "Manufacture- Haberdashery and ready-made clothes. A. Lerenkind"

Nowokolska Rachela

Skałka Sara - shoe store and haberdashery

Słonimska Rachela - grocery store, haberdashery and silk materials

Stawski J.

Szachna

Byśko

Feldbaum Aaron

Feldbaum Herszel

Jagodziński Kalman - hide, shoemaker accesories and kerosene store

Jejna

Jenke

Lejba (Zastawa)

Malecki

Pejsach

Ruda Rajna (Zastawa)

Rudy (Zastawa)

Skałka Abram

Skałka Chaja

Skałka Sara - shoe store and herbadashery

Tabacznik Salomon

Szlocharman

Burnsztejn Abraham

Burnsztejn Berta

Burnsztejn Wiktor

Cynamon Jankiel - purchase of fuelwood, grocery store, beer tavern

Cynenbał

Galpern (Halperin) Joszua - owner of a wood sorting plant, chairman in the Office of the Wood Industry in 1913-1914

Galpern (Halperin) Łazar

Kruhman W. (Zastawa) - wood trade, grocery store

Kuzniecow - Wejner Izaak (Tropinka)

Szerman Abram - owner of a lumber mill (Podolany)

Wolman Kalman

Drozdowski

Góra Judel - meat store, bakery

Kapłański Lejb

Kaznikarska M.

Klejnerman Nachman - meat store, grocery store, herbadashery, kitchenware

Krenicer Gerszon

Norba (Narbar) Abram

Perlman Mosze

Feldbaum Herszel (shoemaker)

Galpern (Halperin) Hersz

Lerenkind Joszua

Schneider Chaim Aaron

Alkon Emanuel

Krugman

Loszewicki Majer

Rejnes Zalman

Sztejnberg Jakub

Szwach Aron

Cynamon Jankiel

Dworecka Chana

Goldberg Szaja

Goldkind Kopel - beer tavern and silk material store

Jabłonowicz Bobla

Lerenkind Izaak i Necha

Sarenka (Krzyże)

Sawczycka Chana

Sawczycka E. (Budy)

Sznabel Zelig

Kreszyn Adam (Abram?)

Lejb Feldbaum

Małecki Chaim i S-ka

Motel Rabinowicz i S-ka

Stawski Józef

Zylbersztejn Mowsza

Cienka Edzia

Cienki Natan - grocery store, haberdashery, iron articles

Grabski Szloma Zelman - grocery store, iron articles, silk materials

Stawski

Tabacznik Salomon - grocery store and iron articles

Watchmakers and jewellers:

Krugman Chaim

Zyngier

Malecki

Horse vendors:

Mejer (Zastawa)

Nachman (Zastawa)

Mechanics:

Galpern (Halperin) Abram

Galpern (Halperin) Łazar

Pomeraniec Chaninij (Zastawa)

NN at the river at the prelonging of today's Sportowa street

Borus M.

Kreszyn Abram

Byszczycha (Zastawa)

Jabłonowicz

Feldbaum Samuel

Kestin I.

Klejnerman Szlomo

Skałka Józef

Bachrych

Enach

Berko

NN (transports the milk to Grudki)

NN with his wife

Bicycles:

Footnotes:

- mid-war times (1918–1939)

Jewish settlements during the mid-war times (1918–1939)

Footnotes: